July 2019

July 26, 2019

Mosaic Art

When I was quite young, someone gave me a kit for creating a mosaic picture. I no longer have any idea what the final product looked like, but I do remember clearly the sense of accomplishment I had in creating something of beauty.

Years later, as I was wandering around in a bookstore dedicated to the arts in their many forms, I happened upon a book about the famous mosaics in Ravenna, Italy. I was, and still am, fascinated by the scope and beauty of these intricate creations. They are amazing.

A number of years after that experience, I was privileged to visit Israel. Now there is an incredible wealth of places and people that one can encounter in Israel, but more than anything I wanted to visit the Church of the Multiplication of the Loaves and Fish, in Tabgha, in order to see in person the mosaic portraying that story that we read in the Gospels. Fortunately, that church was on the tour itinerary. And I was transfixed by the intricacy and beauty of the mosaic. I was indeed the last person to return to the bus.

Today, whether I find it in office buildings, hotel lobbies, or public settings, I continue to be fascinated by mosaic art. What I find to be of such great value, besides the joy I have in viewing mosaics, is the intimate interaction between artist and material, between artist and “canvas.” This is not something that can be assembled in any kind of hurried way. Mosaic art requires planning, great patience, and the ability to see the whole creation while working on a very small portion at any one time.

One of the first arts-related projects that I did at my church was to organize a mosaic workshop. I found a mosaic artist, arranged for her to spend all-day Saturday and the second half of Sunday, directing the creations of mosaics by those who registered for the workshop. We had expected that we would be doing well is we had five or six people who were interested in this art form. We ended up having nineteen people registered for the workshop. This was actually more people than the artist was comfortable working with, but we paired up people and so she was only overseeing ten projects. It all worked well, and as it ended up, people were not only interacting with the materials, but were making creative decisions with one another.

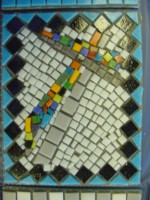

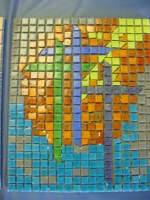

Here are photos of just three of those creations:

As you can see, since we had not done this before, we established a common theme of creating something involving one or more crosses. Remembering that, except for my childhood experience, none of us had ever done this before, the results were remarkable.

Workshop experiences such as this can provide both an intimate understanding of the creative process, and a finished creation that people can see hung together on a wall of the church, and of which they can rightly be proud. Whether it is mosaic, watercolor or photography, such creative endeavors are profound experiences of the arts within the church.

July 19, 2019

Interacting with Artwork

It was a month and a half ago that I made a brief reference to a book entitled, Image and Spirit: Finding Meaning in Visual Art, by Karen Stone. At the end of the book is a resource entitled, “101 Questions to Ask of an Artwork.” These questions serve as a guide to help people to notice things, and to become comfortable in examining a work of art.

As I was suggesting, in last week’s blog, that a close examination of works of art can yield both discovery of the depth of pieces, and perhaps insight into feelings about the topic portrayed, I thought again of these 101 questions. Of course, unless one is writing a scholarly paper about a work of art, one is not apt to use anywhere near 101 questions to engross one’s self in a painting, photograph, or sculpture. However, to select eight to twelve questions to guide one’s examination of a work, could prove to be quite fruitful.

Now since I wouldn’t expect everyone to run out and purchase the book, although I can certainly recommend it, I thought it would be helpful to share just a few of Karen Stone’s questions.

“Who is the artist and when did she/he live? (Is the artist still alive?)”

“When and where was it made?”

“What title would I give it?”

“What is the medium? (Oil paint, watercolor, wood, fabric, paper, ceramic, wax, etc.)”

“Does it look like the artist worked quickly, deliberately, or slowly?”

“Does everything in the artwork look equally important? If not, what draws the eye?”

“Is there a story the artist seems to be telling?”

“Is it a known story, such as a myth or historical event, or is it up to the viewer to figure it out?”

“What story could I make up about this artwork?”

Well, there are ninety-two other questions in her list, but that gives you an idea of the breadth of the examination which she is encouraging people to undertake. One can of course develop one’s own set of questions, and that may be as helpful, or perhaps even more so, depending upon what you are hoping to discover in an artwork.

The value of having such a set of questions is that it gives us a place to begin in our viewing of artwork. It actually encourages us to take a second look at ones that we might otherwise walk by.

July 12, 2019

Art and Literature help us to Engage Feelings and Challenging Topics

Our church book club met last Friday to discuss the book, The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers, by Maxwell King. While I didn’t find the writing style to be near as engaging as other biographers whom we have read, I was grateful to learn a great deal about Fred Rogers, his philosophy, his religious commitment and his work.

One of the central parts of his television show, which was for him a form of ministry, was the idea of listening to children, of welcoming and discussing their questions and their desire to share their feelings. For him, there was nothing wrong with any feeling. It was only a matter of what one does with that feeling. For example, it was okay with him for a child to be mad, and it was good to talk about why the child felt that way, but then one’s response needs to comes from understanding things better.

It seems to me that most adults could benefit from such an engagement with feelings, and with uncomfortable questions. I asked the book club members to suggest topics that we as adults tend to avoid. Although a couple of people said that they had grown to learn that it was best not to discuss religion and politics in many settings, because of the divisive nature of these subjects, no one identified any additional topics that we tend to avoid.

So, while I prefaced my remarks with the stated understanding that I may be stepping on the toes of some in the group to bring this up, I also said to them that it has always been an interest for me that so many people refrain from talking about death. Now I can understand that avoidance in some ways with people outside the church, but within the church that should be a very different conversation. I mentioned that many people, both inside the church and beyond its walls, talk about death as “someone passing.” In the best sense, I guess that means someone has passed from this life into another one. But in the general use of the phrase, it seems to me to be a way of avoiding talking about death directly. Especially in the church, we should be willing to meet death head on, to claim the sadness we feel, to acknowledge that we hurt inside, but to also claim the faith we say we hold, that death is not an end, it is a new beginning. Death is a natural part of life, and life continues in a new and most beautiful way.

Okay, I don’t want this to sound like a sermon. My point is that a book such as this became a way for me to approach a topic with people that I think can be difficult for them to think about and reflect upon. Novels as well, which are filled with characters who are not us, can became excellent vehicles for engaging in conversation about other topics which are difficult for people to discuss. For example, when we read The Red Tent, it opened the door to discuss women’s roles, sexuality, and more. We may not usually approach such topics, but when we are talking about them through the viewpoints of the characters, it becomes easier to do so.

In the same way, visual artworks often provide an alternate way into an exploration of feelings, emotions and diverse topics. Just as Jesus wanted his listeners to think about who is acceptable and who isn’t, who is my neighbor and who isn’t, in telling the parable of “The Good Samaritan,” so we can often more thoroughly discuss those topics as we move beyond the familiar words he spoke into visual depictions of the events of the story. An examination of Da Vinci’s “Last Supper” can provide an interesting foray into the personalities of the disciples. A close look at their faces and body positions can tell us what Da Vinci thought about their reactions to Jesus’ words at that meal. This can lead to a discussion about the ways in which we are faithful, questioning, preoccupied with our own agendas, or just plain at a loss to understand things.

Preparation for such discussions is of course essential. My thorough reading of The Good Neighbor, and my own reflections on the content of Fred Rogers’ work, was important in order to form the discussion questions for the group. In talking about novels, it helps to do some background research in order to understand what the writer may be communicating through her or his characters. Research into the nuances of artworks helps to inform those conversations.

But these preparation efforts can produce a depth of conversation that many of us are unwilling to engage in without such prompting from works of art and literature. These discussions can truly become gifts that we offer to one another.

July 5, 2019

Painting the Spiritual

We hold most of our church book club gatherings at the home of a member who finds it difficult to get out, but who loves to host the book club and to see everyone for those couple of hours. It is invariable my good fortune to sit on the couch opposite this person, which also means that I am facing a great painting that hangs on the wall near her. It is a wonderful work by Marc Chagall, and I am always moved by the flowing of spirit within the colors and depictions in the work.

As I was further reflecting on last week’s blog, I thought about Chagall and this work of art, as well as of the art and writings of Wassily Kandinsky. I was introduced to Kandinsky during the years of my doctoral work, and found that his paintings, especially his later ones that are abstract, fill me with a sense of a deep spirituality. I was then grateful to discover and read his brief book entitled, Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

I am fairly certain that there are people for whom the art of Chagall, and the abstract works of Kandinsky, are just wild expressions of something other than art. But discerning God’s Spirit takes patience and exploration. In the same way, the depth of the works of Chagall and Kandinsky require a similar sort of commitment to discerning the movements of spirit that are there.

While Chagall is more representational than Kandinsky was in his later works, both of them employ vivid colors, a sense of movement, of life, and that translates for me into a flowing of spirit, and in particular of God’s Spirit. As I wrote last week about the reflections of James B. Janknegt on his own art, I shared his thoughts about the challenge of depicting the spiritual through the concrete world. In their own ways, I believe Chagall and Kandinsky do bring the spiritual to life as well.

In the conclusion to his brief book, Kandinsky writes about there being three different sources of inspiration for his works. The third one, which he relates as being depicted in a “Composition,” is “an expression of a slowly formed inner feeling, which comes to utterance only after long maturing.” (p. 57) This sounds remarkably similar to a slow, patient, deeply sought-after experience of the Spirit of God, made known to us in prayer, meditation, scripture reading and intentional reflection. Such patient reflection on works of art, especially those more abstract works that can seem at first glance to have no meaning, can prove fruitful to us as well.